Joan Rypkema speaks every word clearly, as if she’s writing.

No crutch words for Rypkema.

No — like, you know, so.

She is, after all, a retired English teacher.

And she now lives quietly in a quaint little log cabin in Great Cacapon.

But things were everything but quiet in the early 1970s, when Rypkema began teaching English at Berkeley Springs High School.

Rypkema was at the center of what many called the biggest controversy in Berkeley Springs since the public lynching of Samuel Crawford in 1876.

Crawford — accused of horse thievery, carrying concealed weapons and shooting at a police officer — was lynched without trial by a mob of 25 men who dragged him out of jail and hung him from a tree.

A photographer had taken a picture of the hanging Crawford.

S.S. Buzzerd, the founder of the Morgan Messenger, wrote about the case in the paper in 1958, and ended his article with this: “May there never be another lynching, here or elsewhere.”

Almost 100 years after the public lynching of Crawford, they went after Rypkema.

And all she did was teach English.

Rypkema was born on a farm in Rochelle Park, New Jersey.

Her parents were immigrants — father from the Netherlands, mother from Denmark.

She studied English literature at Seton Hall University (BA) and Purdue University (MA).

She moved to Berkeley Springs in 1969.

How did she get here?

“A friend of mine from high school in New Jersey — Joan Kuiken — got a job as a counselor at Berkeley Springs High School and she asked me to drive a U-Haul with her things here,” Rypkema says. “I did. At first I thought — thank God I’m just staying here for three days. But then I decided to move here also.”

The two Joans lived together in Berkeley Springs for years.

Rypkema taught English in the Berkeley County school system before she was hired in 1972 to teach English at Berkeley Springs High School.

She was an unconventional and popular teacher with the students. (One student, Marcia Updike, wrote at the time that Rypkema “encourages her students to be themselves and to have feelings — not to be a human machine knowing only facts and figures.”)

Popular with the students, but not necessarily with the parents.

One problem was Rypkema’s name.

“One member of the community told me that my name — Rypkema — sounded Russian,” Rypkema says. “And therefore I must be a Communist.”

Another problem was Rypkema’s openness with her students.

Rypkema said she was fed up with the graffiti in the bathrooms — in particular the F-word.

“One day I wrote the letters F U C C on the blackboard,” Rypkema says. “And I tried to explain to the students that one derivation of the word they were scribbling on the walls of the school had it’s origins in the Civil War. When soldiers died from contagious diseases, their medical papers were “filed under category contagious — FUCC.”

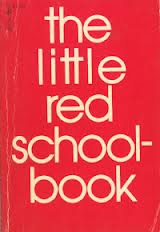

But then came The Little Red Schoolbook by two Danish schoolteachers — Soren Hansen and Jesper Jensen.

It is actually little — three inches by five inches.

And it is actually red.

It gives candid advice to students about sex, drugs, parents and teachers.

The book was banned in Italy and France and for a time in Switzerland.

Mostly, the book tells a version of the harsh truth.

On drugs: “Drugs are poisons which can have a pleasant effect.”

On sex: “People go to bed with one another for many reasons.”

On the education system: “Instead of helping you to develop as an individual, schools have to teach you the things our economic system needs you to know. They have to teach you to obey authority rather than to question things, just as the exam system encourages you to conform, not to be an individual.”

On parents: “A teacher who wants to let you try something new can also have problems with parents.”

Miss Ryp, as the students called Joan Rypkema, wanted the students to try something new — like having the opportunity to order and read books like The Little Red Schoolbook.

Rypkema makes clear that she didn’t assign The Little Red Schoolbook, she didn’t recommend it, and it was not required reading in her class.

Instead, students were given the opportunity to order it, as they were given the opportunity to order other books, for outside reading.

The parents had to sign the book order form and 28 students out of more than 100 students ordered the book. The program was sponsored by Scholastic Magazine.

But that didn’t stop the parents from organizing so that she would not be rehired for a third year. (At the time, Morgan County teachers would not be granted tenure until they had completed three years teaching at the school.)

At a crucial community meeting at the Berkeley Springs High School cafeteria in April 1973, more than 200 people attended.

John Barker, a reporter for the Hagerstown Morning Herald, reported that while the speakers at the meeting were evenly divided between those who sided with Rypkema and those against, those opposed to Rypkema outnumbered those in favor in “boos, applause and numbers.”

Barker reported that one middle aged man rising on his feet and shaking his finger said — “that book goes against all the precepts of morals, religion and politics we know of — everything that intelligent people are for, this book is against.”

Barker reported that the loudest and longest applause at the meeting came after school board attorney Samuel Trump made a speech saying “the book explains things that are against the law in West Virginia.”

“Trump said he was referring specifically to certain sex practices which constitute felonious sodomy in the state. ‘It may be all right in some states,’ Trump shouted at the approving audience, ‘but it isn’t here. It has no place in a junior English class as long as the state legislature has spoken to it in that manner,’ Trump said.”

In the spring of 1973, the Board of Education refused to rehire Rypkema for a third year. But the class of 1974 was outraged at the decision and asked Rypkema to be the commencement speaker for their June 4, 1974 commencement.

The School Board said that Rypkema would not be the commencement speaker. But the students said — No Rypkema, No Commencement. And the students won.

Rypkema secured legal counsel and sued the School Board in federal court in Elkins to get her job back. As the case proceeded to trial, the writing was on the wall — the media was all over the case and Rypkema was going to win. That’s why the School Board decided to settle the case.

As a result of the settlement, Rypkema was rehired and began teaching again in 1977. She taught until her retirement in 1993. (Although it was icy the first few years back. Rypkema says the first year back she was assigned to teach English as a second language. She was assigned to teach one Vietnamese student in a small storage room at Berkeley Springs High School.)

Rypkema shows me a notebook where she kept notes about the case. On the back side of the notebook is a sticker that reads: “Will it matter that I was?”

Yes, it did matter.

Rypkema’s case drew national attention.

Scholastic Teacher magazine ran a long story in its April/May 1974 issue titled — “A Teacher vs. a Town.”

In the face of such hostility, Rypkema could have picked up and just moved away from Morgan County. But she stayed and fought back. She defended the her First Amendment rights in court. And she won.

In the end, the authors of The Little Red Schoolbook had it right: “A teacher who wants to let you try something new can also have problems with parents.”